Hi everyone!

Welcome to the first installment of A Time to Talk, a series where I will interview friends and artists I love and admire. The title is stolen from a Robert Frost poem about friendship, and the hope is that these conversations will offer a time to talk that goes beyond quick “how are yous” or boilerplate check-ins. First up is my sister-in-law and friend Kate Schneider, who, if you couldn’t already tell, I’m pretty obsessed with.

Kate is a brilliant artist, writer, and therapist who has published two graphic novels – Dew Drop Diary and Headland. She is also a person living with brain cancer. In April 2022, two weeks after her 30th birthday, Kate had a seizure that led the doctors to discover a tumor in her brain. Shortly after this discovery, she had brain surgery and began radiation and chemotherapy treatments that would last for over a year. This past August marked one year since Kate’s last chemo treatment, and though her cancer is now stabilized, she is still grappling with the aftereffects of this life-changing diagnosis.

On a sweaty August afternoon, with iced coffee and a plum torte in hand, I went over to the house Kate shares with my brother, and we talked about what her life and work look like now, two and a half years after her seizure. Our conversation lasted for close to two hours, so even with editing and condensing the interview, you may still have to expand this email in your browser to read the full thing (or read it on the Substack app). This conversation meant so much to me — I hope you enjoy it.

Grace: It's weird to “interview” you, but it'll be fun. August marked one year since you finished chemo, but before we get into that, I wanted to know how you would describe yourself as an artist.

Kate: Good question. How would I describe myself? I like mixing mediums, whether it's gouache, torn paper, clay, paint, or cyanotype. I like to play with themes in the natural world – the natural world is a big source of inspiration, and I also make picture books.

G: I know you prefer the term picture books over graphic novels. Why is that?

K: When you look at the cover of a graphic novel, they're always lushly colored, but the cover is not representative of what’s inside. You open [the book] and it's black and white – it's such a letdown. There is so much more creativity in children’s picture books than in adults. I think we all deserve more playfulness. I'm trying to — and I'm not the only one doing this — bring that playfulness to adult work, so calling it a picture book feels more aligned.

G: How did you land on the medium of graphic novels or picture books as an artist?

K: I was raised with children's books that my artist mother very specifically curated. I wasn't raised in the world of comics. I don’t think I ever actually read a graphic novel before writing my own. I think that's what permitted me to do something different. I studied poetry in college, and that combined with the picture books I was raised on became the books I’ve written so far.

G: And were you always drawing, too?

K: My mom and I had a few rough years when I was in high school, and the only time we could be peaceful together was in this nude figure drawing class at the Waldron Arts Center. It was the only three hours we could talk and share something without fighting. It was so healing, and I kept drawing.

G: So you were drawing in high school and you were writing, but they were still separate at that point. When did you bring them together?

K: I was inspired by [artist and graphic novelist] Aidan Koch because I thought she did something more like a children's book. But I was also kind of frustrated by her because I didn't think she could really tell a story. So my goal with Headland was to tell a story with pictures.

I began [Headland] during my senior year of college, and it started as a totally different thing. I was in it at first, but once I took myself out, it gave me permission to make it fiction. It needed to be fiction so it was free to be what it wanted to be. The process felt kind of magical and mysterious, like the book was two steps ahead of me. I like it when projects seem to know more than I do. It's like following the tail of an animal into the woods. You never find out what the animal is. You see the tail behind leaves and trees, and if I can follow that tail or footprints, it will take me somewhere. I want the story to be ahead of me.

G: There was so much synergy to Headland. Ruth, the main character, was based on an amalgamation of your Grandmother, who had a stroke, and Audrey, a woman you worked for with dementia. Your grandmother's from Bath, and then you learned Audrey was also from Bath.

K: The whole book is based in Bath. My Grandmother passed one week after I met Audrey, and I had already been working on Headland for a few years at that point. Audrey reminded me so much of my Grandmother. They both drank Bristol Cream Sherry, for example. It made me feel like people occupy bodies, but they don’t totally go away when they die. The connection felt too serendipitous for there not to be some kind of God involved.

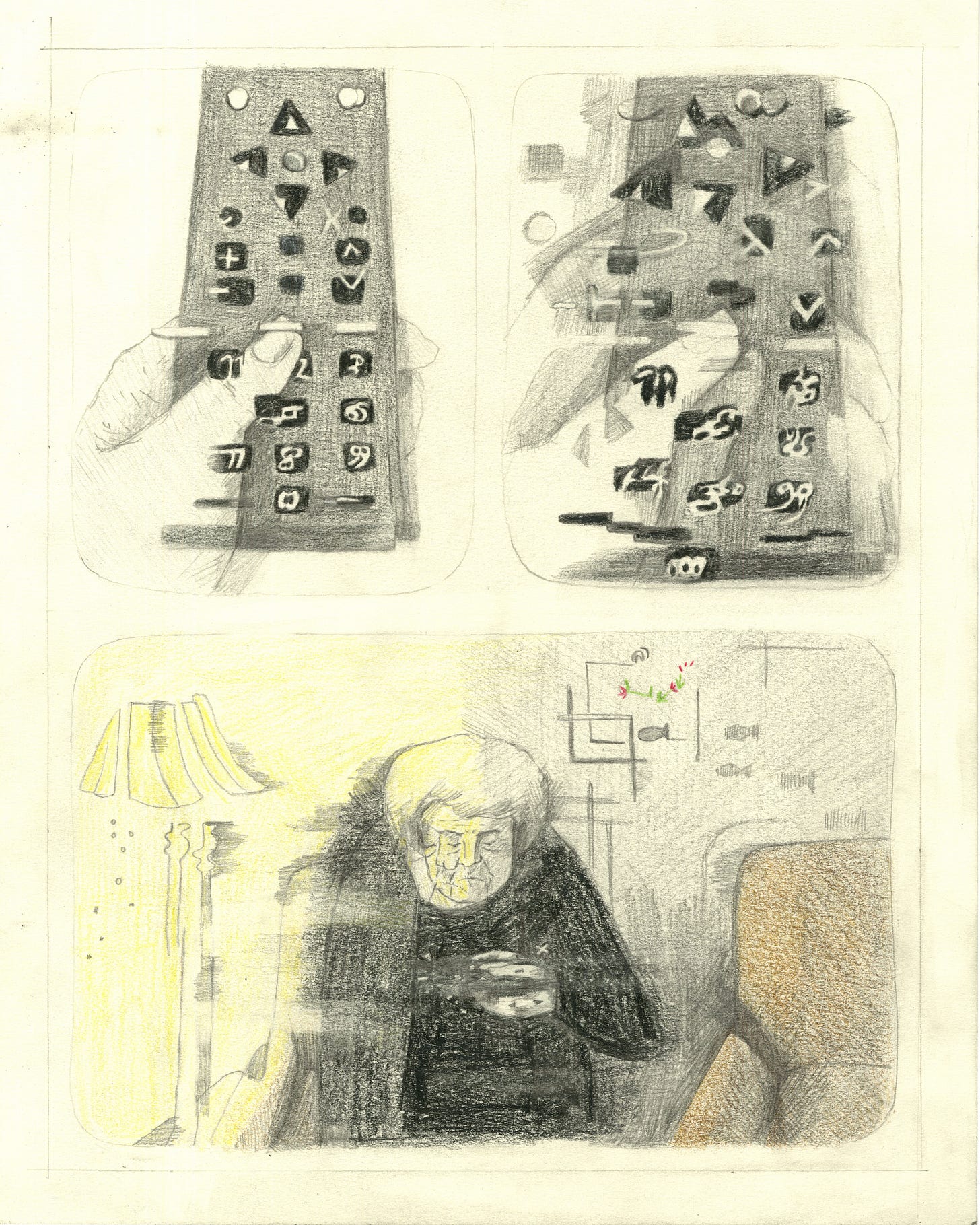

G: In Headland, Ruth is dealing with the aftermath of a stroke. She wakes up in the hospital – afraid and confused – and to cope, she retreats into, as you put it, “the wilderness of her own mind.” There's not a lot of language in the book — there's basically no text, and it's almost all images.

K: That choice was rooted in science. I wasn't making shit up. When I was researching strokes and dementia, I learned that when there is trauma to the brain, language is suppressed and images get illuminated. I wanted to communicate that [in Headland]. I read [brain scientist] Jill Bolte Taylor’s book about her stroke. She said things like the energy of the wall was merging with the energy of my hand, which inspired the image of Ruth in Headland when she’s having her stroke, and the remote is mixing with the hand and everything gets jumbled. It’s not unlike when I had my seizure — I felt like I was being pulled to a different place and there was a confusion of matter.

G: This is something you've talked about before – how post-seizure and brain surgery, you felt more connected to Ruth.

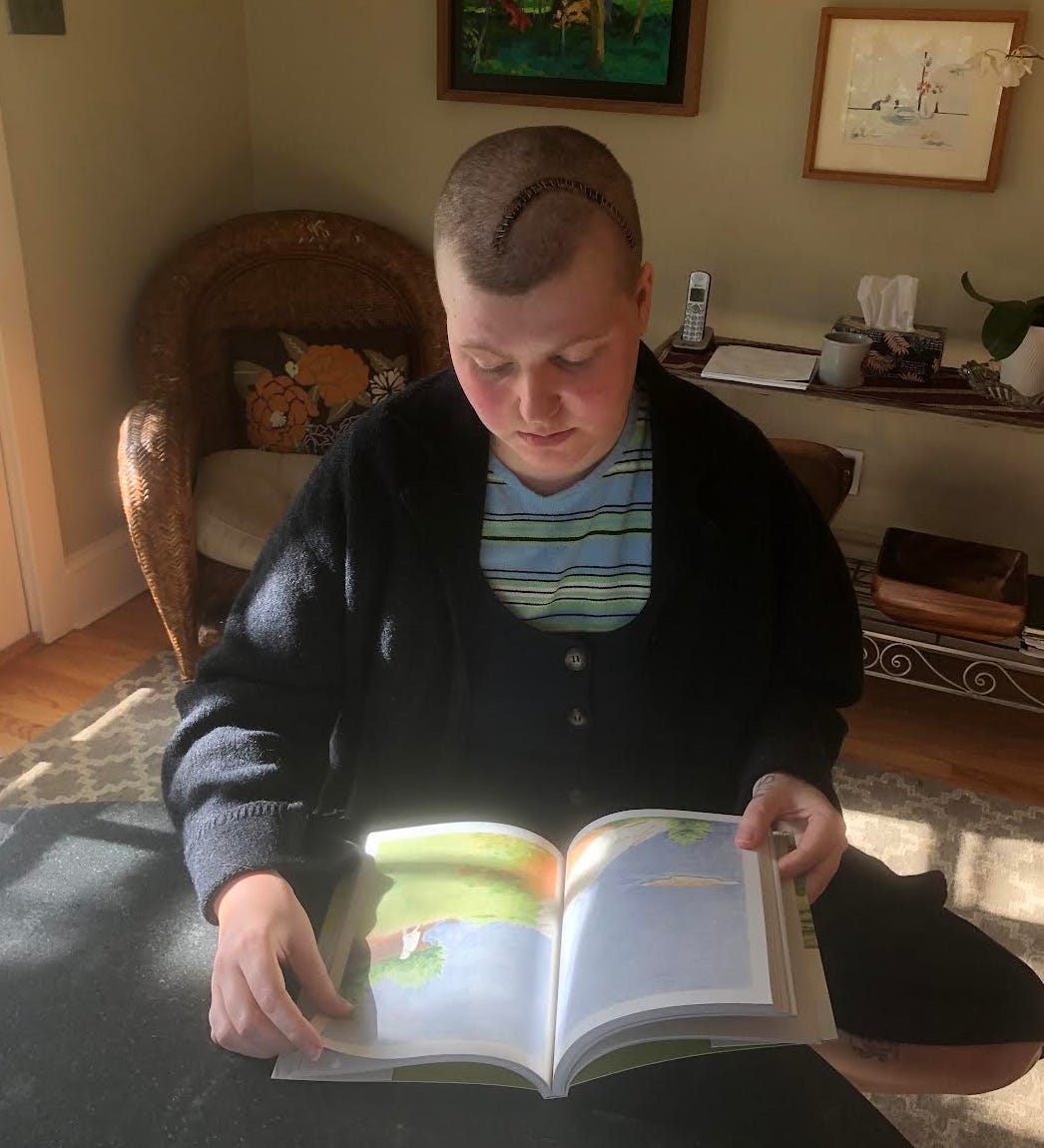

K: I think part of it was my inability to find language. My scope was so narrow, but it was sort of self-protective. I wasn't scared when I came out of surgery. When there's trauma to the brain, you don't know what other people see. I didn't realize that my face was busted and my head was half shaved and had staples in it. I mean I looked kind of punk, but my brain trauma took away the vanity that we usually live with every day. I was like, “I look good,” even though I definitely did not look good. It was freeing in a way. I felt like I could only focus on one thing — like the primacy of brushing my teeth was all I could think about. It would fill up my whole head, and it was sort of meditative.

G: Did you feel like you still knew how to do those things?

K: It felt like learning how to do them for the first time. It took all of my energy to brush my teeth, all of my focus was on each tooth. The world slowed down. And I don't know the scientific differences between seizures and strokes, but with trauma to the brain, your brain has to restart and relearn so many things. Depending on how old you are and how severe your stroke or seizure was, you have to relearn how to talk, how to move, everything. My Grandma re-taught herself to write after her stroke — she was so determined.

G: You've had to do a similar thing in teaching yourself to find your words again.

K: It was so frustrating. I would scream because I couldn't find the words. I got tangled up in my own language. It felt like the itchiest sweater. When I was a baby, I would watch my Dad talk and imitate his mouth. Language has always been a crucial part of my identity.

G: When you felt like language wasn't in your grasp, what did you turn to? I remember you watched a lot of Harry Potter and Pride and Prejudice, which was, of course, essential. But what else helped you?

K: Walks in nature. I felt like the trees didn't need anything from me. The leaves and the flowers didn't either. I felt such peace, and I felt so safe. Nature wasn't asking anything, and it hadn't been taken away. My mom taught me how to look at things closely. Even when I wasn't drawing or painting or making anything, my eyes had been trained to look at things closely. So when I was recovering from surgery, I had the eye of an artist, which meant looking at things very closely, looking into the petals of a flower, looking at every new shoot of spring. My surgery was in the springtime, and I felt like I was waking up with the world for the first time. I was a baby. I could barely speak. I was excited about everything.

Talking with friends was also so helpful. I got a speech therapist, and I was like, “You don't know how much I want to talk!” It was talking with friends that helped. So much of the experience of having brain surgery and cancer made me feel like a baby again. My baldness, my fatness, my language, my parents being there — I felt like an infant. It was a big point of empowerment to talk to my friends. It was my way of feeling some semblance of independence, and it felt very radical in that moment.

G: And your friends don't care if you say the wrong word or if you're searching for a word, maybe they can help you find it.

K: There's no judgment. There was no judgment from my parents either, but I knew they were so concerned. And of course they were, but I didn't want to be looked at in that way.

G: They were feeling afraid while you were also feeling afraid.

K: I had a therapist right after cancer, and she told me about this dump-in, dump-out model. You dump out to the people who are further outside the person who's at the center. It felt nice to dump out to my friends who were further outside. My parents and I were kind of enmeshed. I couldn't figure out how to differentiate between me and my parents. I felt like my pain was their pain. It felt too blended. And that's what it’s like when you’re a baby, too.

G: How did you feel with Will? [My brother and Kate’s husband].

K: I remember having a full-out tantrum, hyperventilating, and screaming in the car when I wanted McDonald's about a week after my brain surgery. That was a major moment haha. But we’ve only been together since 2019, and the experiences we've gone through, the trauma we've gone through — most people don't go through, if ever, for another 30 years or so. I think it has made us stronger, and also probably put a lot of serious thoughts on our plate before we were ready to think about them. We were freezing our embryos before we even got married.

G: I remember having dinner with Will right before you had your seizure, and he told me he was planning to propose to you during your trip to England over the summer, and I was so excited. But then a few weeks later he proposed to you in the hospital instead. It was always going to happen, but the diagnosis accelerated things.

K: Definitely. Did I see you the day before my seizure?

G: I remember it so vividly. You came over for dinner, and you seemed off. We were all laughing about how loopy you seemed, and then the next day, you had a seizure and they found the tumor.

K: I was also studying for my licensure exam at the time, and I remember not being able to retain any information. I was laughing like, ‘Haha I'm so dumb,’ but secretly I was really, really nervous. I was interviewed around that time, too, and they had to edit the shit out of it because I froze. I was surrounded by nothing but white space. I’ve never had an experience like that, and it was so scary.

G: How did you explain it to yourself at the time?

K: I knew something was wrong. I wrote a list in my diary of possibilities — maybe it was because I was depressed or I had just finished this soul-sucking job in a windowless room. I was really scraping the bottom of the barrel to find excuses. But it was brain cancer. I was somewhat relieved. At least I'm not boring or suddenly dumb – it's a huge fucking tumor.

G: Is there any way to know how long you were dealing with that?

K: It's so hard to know. I’ll go through my phone looking at photos trying to understand the timeline. It’s kind of like a breakup where you're trying to find all the places it went wrong, but what's that really going to do for you? At most, it'll give you a semblance of control, which I'm reminded daily doesn’t exist.

G: Something we talked about the last time we were together was that you were the youngest person in the radiation room, and how that changed your perspective.

K: Hospitals are the coldest places to exist. The radiation room is the saddest, most sterile environment and everybody is over 50. There's a children's room for oncology and it's so fun — there is nothing like that for adults. The children’s unit needs to share the joy. It's the same idea as picture books — we all deserve portals of play. Even adults, and particularly adults receiving radiation. So that's a separate thing. But being in that radiation room changed my entire perspective on my age. People keep talking about how old they are, and I’m like, you’re not old. I was young in that room. I want to remind everybody, and this sounds a little preachy, but we're not old. We’re going to look back and wish we were this young.

G: And you were reminded of how young you were because you were literally the youngest person in the room with this incredibly scary diagnosis.

K: It’s interesting, now that my hair is grown back, people don't immediately see me as a patient. I’m just another 30-something. I mean, it's good that my hair has grown back, but it's weird because I want people to know that I have brain cancer. I've been through some shit, and maybe I'm being selfish, but I want people to understand that.

G: I don’t think that’s selfish. You've been through an insanely traumatic two and a half years that has fundamentally changed you. It makes sense that you would want that to be recognized and understood.

K: And every three months I'm reminded of it when I get an MRI. I don't know if this is fair to say because I don't know the future, but I don't think the anxiety of living with brain cancer will ever fully go away.

G: I wanted to ask you about that. Every three months you have to stop whatever you're doing and get an MRI to check if the tumor is back. How does that show up in your life?

K: Crippling anxiety. I can't think about anything other than it. It feels like an animal is gnawing inside my chest, eating itself, trying to get out. My friend Kasra said something thoughtful about it, which was, “You'll get better at living with brain cancer.” And that has already proven true. So at this rate, I'll be crushing it in a few years.

G: I know a lot of people can feel afraid of saying the wrong thing to someone with cancer. After you were diagnosed, did people say anything that was not helpful?

K: When people first heard, some misunderstood my cancer diagnosis. They said, ‘Hope you get better soon,’ or ‘hoping for a speedy recovery.’ But it's not going to be a speedy recovery. I’m going to get an MRI every three months for the rest of my life. Maybe every six months – but that's as good as it can get and it’s still a long way away. Also, the language around cancer that's supposed to be harmless. She lost her fight and all of the war language, “it’s a battle” or “she’s a cancer survivor.”

G: Do you align with that at all?

K: I don't necessarily align with survivorship. I'm a person with cancer, and I don't want that to define me, but it's a huge part of me. I'm still working through what that means for me, but I want full ownership of it. That language makes it feel like the cancer industrial complex. Each person gets to say what cancer means to them and has done to them. For me, there's something kind of minimizing about the label of survivor or victim.

G: The way we often think about cancer is black and white: you’re either a cancer survivor or you lost your battle. But for you and many others, it’s ongoing.

K: I hate the phrase, “She lost her battle with cancer.” Why do we say that? Nobody wants to lose their battle or fight so bravely. I know it comes from a good place of wanting to control things when they're bad, but I don't want to be a part of that.

G: We are often so afraid to talk about cancer and death that we speak in euphemisms or platitudes. We’re quick to say, “She’s a fighter! She’ll get through this!”

K: And that's basically a way of saying, I don't want to hold your pain.

G: I was talking to a friend when you were first diagnosed, and I said, “If Kate dies, I'm so scared my brother is not going to be okay.” And my friend responded, “He might not be okay. But eventually, he will be, and you will be there.”

K: There's so much solace in saying: it might not be okay.

G: Was there anybody that was able to hold the real possibility of you not being okay?

K: My parents were so close to me, and they couldn't tolerate it themselves, which is totally fine. I did talk about it with my therapist. From the beginning, I was researching Buddhism and reading When Breath Becomes Air because I was like, “I need to understand death and I need to understand it now.” But then I realized that wasn’t going to work and it was very humbling — I wont understand death until I die. Sometimes cancer and death are hot on my neck and sometimes they’re taking a leisurely walk behind me. It’s always different, but it’s always there.

G: You’ve also talked about how living with cancer has made you more in tune with God or mysticism or whatever you want to call it.

K: It's so arrogant to believe that this realm is it. Have you looked at birds? Have you looked under the water? Have you looked anywhere into the sky? How the hell do we walk around knowing that this is it? There's no fun or pleasure or mystery in that life. I love to imagine other worlds. It makes me feel so at peace to think of no people anymore. I know it makes people anxious, but I feel at peace.

G: You clawed at the edge of that — of no more me, no more people.

K: [Cancer] has made me less afraid of my own death. I'm still terrified of other people's deaths. It’s not that I want to sacrifice myself — I don’t want to be a martyr. It’s that I don't want to be in pain if other people die.

G: How has your approach to your work changed post-cancer diagnosis?

K: I think my goal is to make it more free, which is so hard. It takes a lot of work to let go. When what I’m creating is working, it feels like it’s happening to me. But really, the work is in me and it’s about taking the time to uncover it, like an archaeological dig. I also really suffer from imposter syndrome. Will I ever make anything good again? But I think the goal for me is to let go – no one has that much time on this earth, so I'm going to let some shit go.

G: What are you working on now?

The goal with the book I’m working on now — Cave of Seeds — is to make an illustrated folk epic from the future. I always like to bite off more than I can chew with projects because I want to live inside this project for a long time. So I’ve done it to myself — I'm going to make a fucking illustrated folk epic.

G: Now that you’re one year out from finishing chemotherapy, what's something you're taking with you in life, work, and art?

K: Hope. It's not always that easy. I want to be brave. I think a big part of courage is trying again. If I get pregnant and have a miscarriage, try again. If I have a drought with my book, try again. Life will rattle you, and it has, but I want to be fearless, even though I’m not. I want to keep trying.

To learn more about Kate’s work and follow along as she creates Cave of Seeds, visit her Patreon.

As always, thank you so much for reading. If you liked what you read, I hope you’ll consider leaving a comment or “liking” this post :) I plan to do more interviews in the coming months, so if you have anyone in mind you’d like to see here, let me know!

Such a fascinating and beautiful interview Grace.